PERIPHERAL CENTERS

Project: Peripheral Centers

Class: Advanced Studio, California College of the Arts, Architecture Division

Date: Spring 2016

Instructors: Neeraj Bhatia

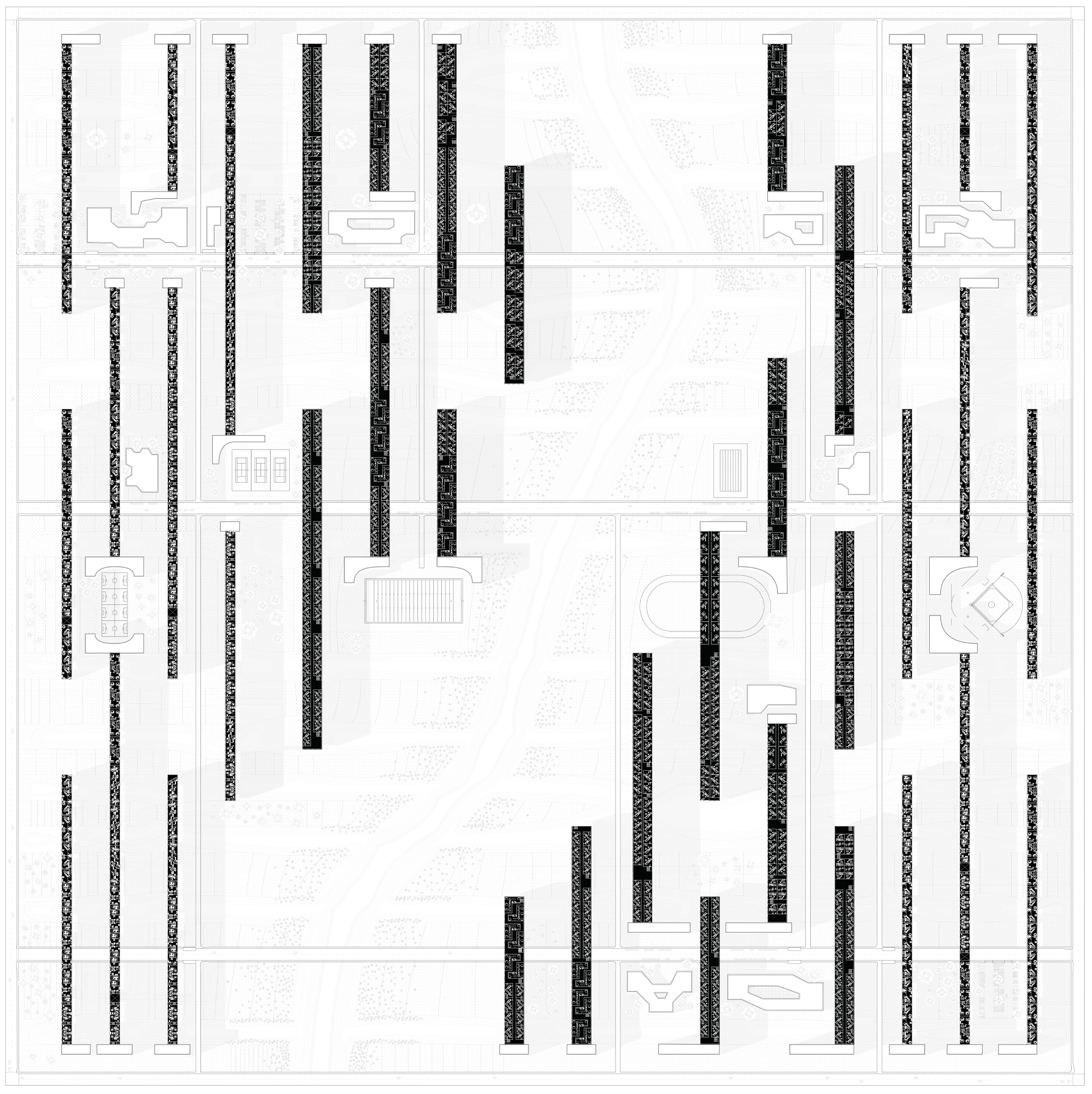

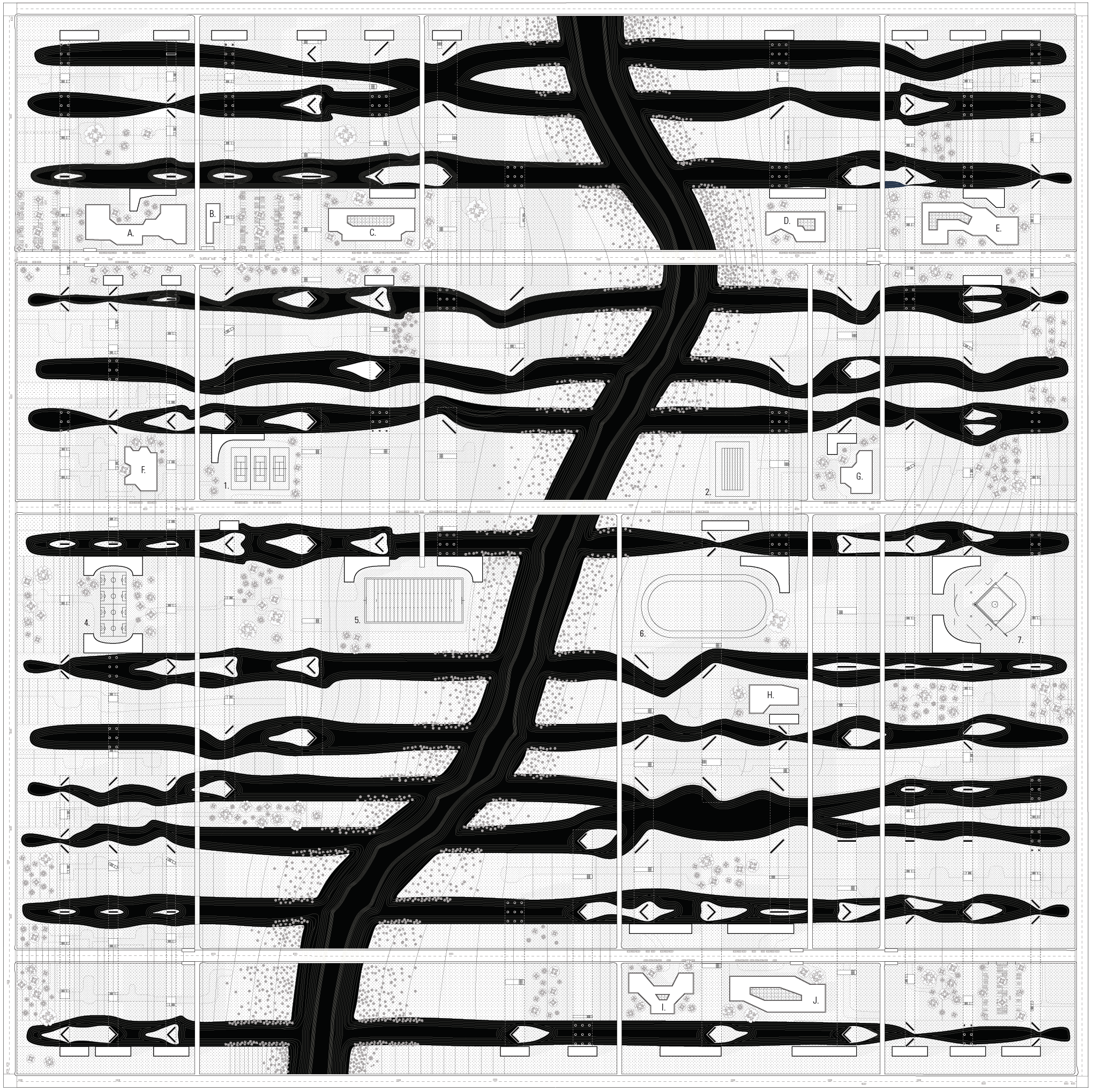

Peripheral Centers explores how architectural form can promote economic, social, environmental, and political equity by integrating urbanization with water management at multiple scales. The studio focuses on Stockton, a deprived logistical hub of California’s Central Valley, and the promise of its future through the development of high-speed rail lines.

FLOW OF PEOPLE

California has embarked on an ambitious plan to connect major population centers namely the Bay Area, Los Angeles Region, and Sacramento with a high-speed rail (HSR) network traversing the Central Valley. The territorial implications of the high-speed rail are far reaching, including the redistribution of populations, economies, industries, and ecologies along with the potential to diversify the valley’s economy to make it more resilient. While the Central Valley is hoping to shed its isolated character and reap the benefits of spatial integration, a byproduct of connectivity is extension of the periphery of metropolitan centers such as San Francisco and Los Angeles into this former hinterland. The bedroom communities that border the Central Valley will become new peripheral centers.

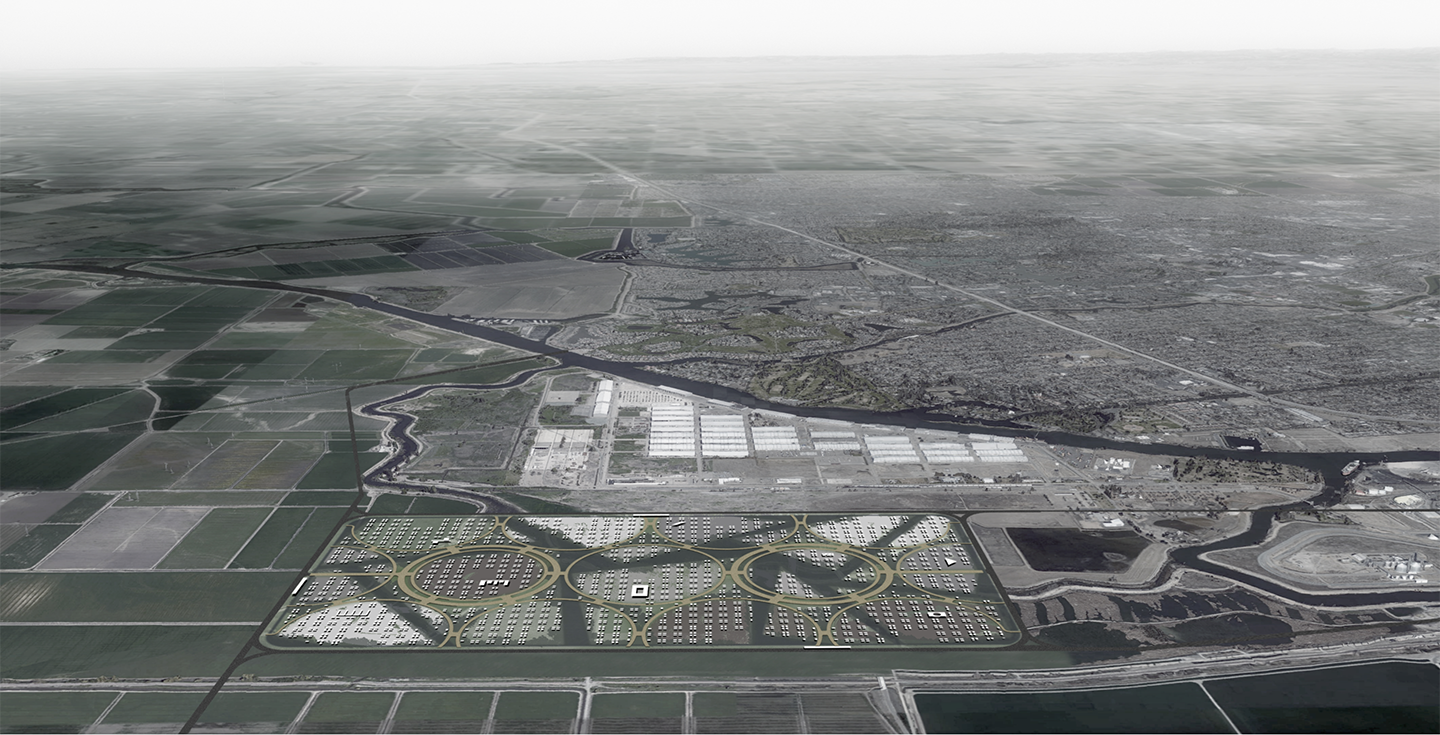

We will explore the potentials and challenges of HSR by focusing on Stockton, one of the new hubs of infrastructural investment and urban development that will grow around the rail network. Stockton, a modest city approximately thirty minutes east of San Francisco by HSR seems to have won the geographic lottery, becoming a hub connecting east-west to north-south high-speed rail lines. The prize in this case is urban growth.

FLOW OF WATER

This is not the first time Stockton has won such a lottery. Located within the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, Stockton once thrived as a major inland port. The city’s origins are intimately tied to logistics, its modern history beginning as a hub for the Gold Rush. Even before this, the extensive waterways of the Delta that run through the city were navigated, settled around, and fished by the Miwok first nations. By the mid-19th century, it was a regional transportation hub primarily for agricultural products and in the 1930s a deep-water channel was carved through the Delta to make Stockton a major inland port. More recently, Stockton’s central location relative to both San Francisco and Sacramento, coupled with its inexpensive real estate, has positioned it as a base for regional operations for several companies.

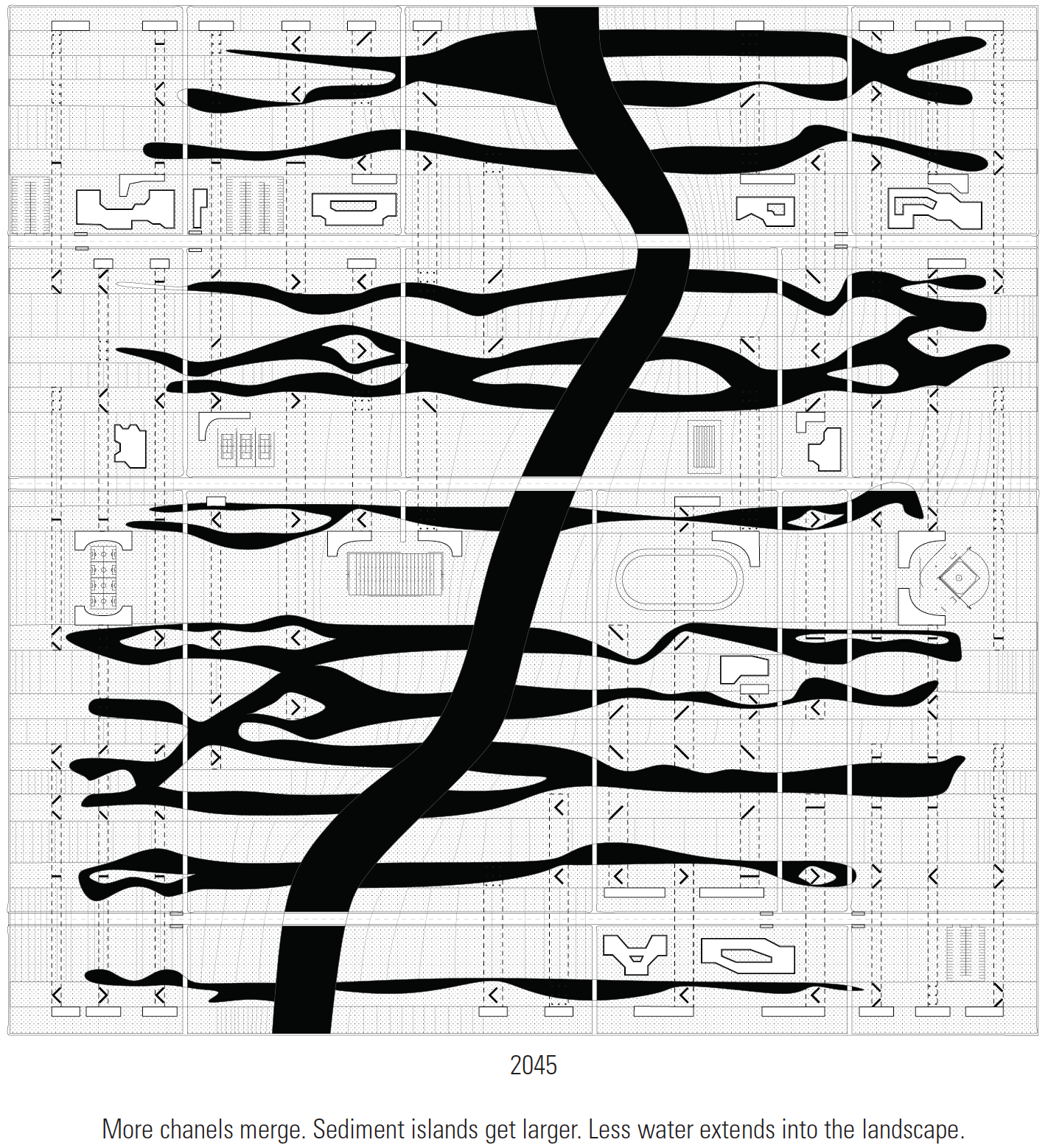

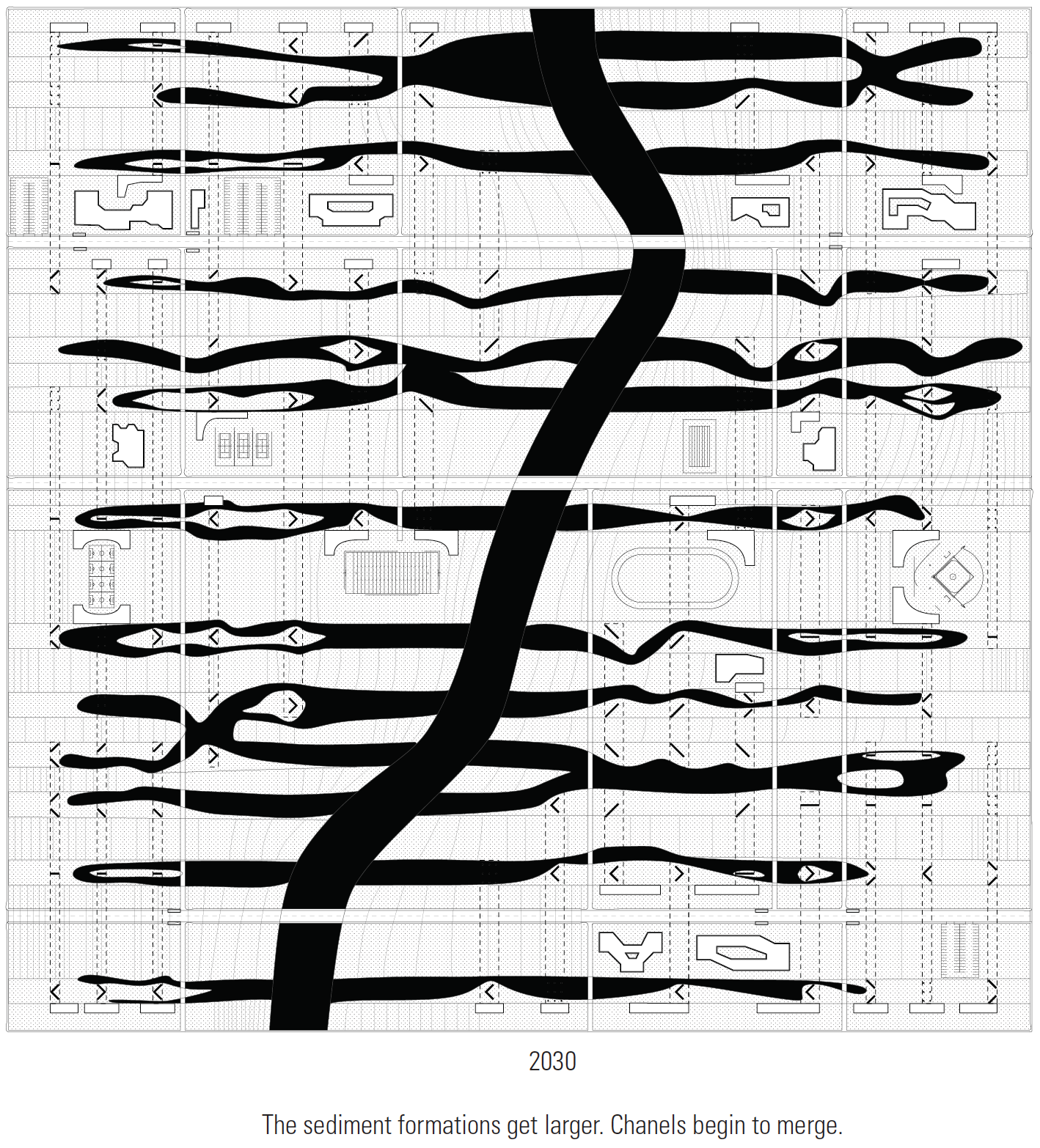

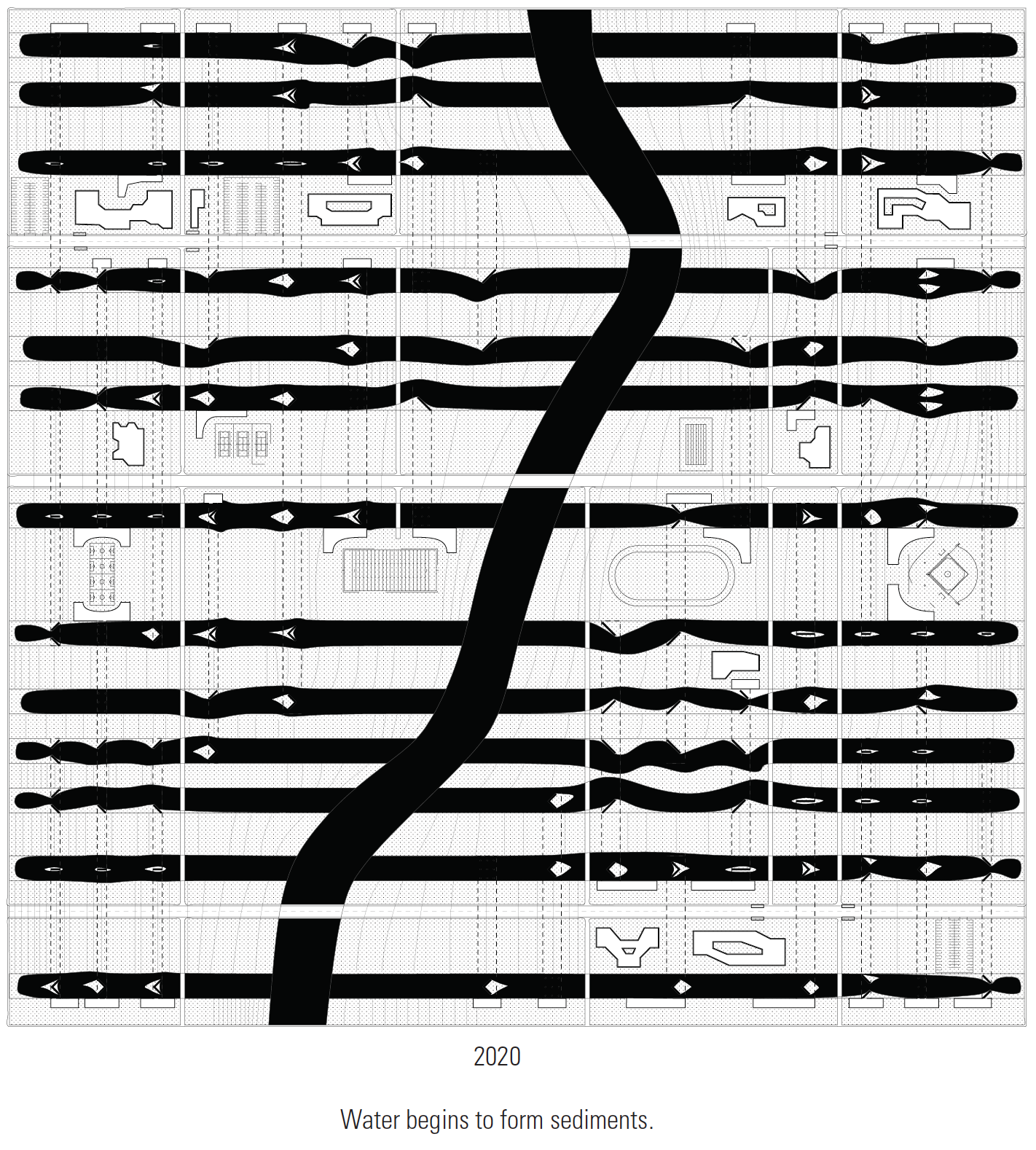

While the urbanization of the city and the agricultural productivity of the land has incited the infrastructuralization of the natural flows of the Delta positioning nature as a medium to control today we are witnessing the ramifications of such practices. Like migrating populations of the bedroom communities, the Delta moves between the Bay and the Central Valley and is constantly in flux. Its territory has become the meeting ground for conflicting forces in California suburban development, environmental politics, the changing economics of agriculture, the continual demand for water, and transformations from climate change. Stockton’s impending development has the potential to threaten the future of the Delta including its ecologies and associated economies. While the current population of 300,000 residents is destined to grow exponentially, there is little vision for how this growth should occur.

FLOW OF MONEY

Stockton’s economy has fluctuated dramatically due to its dependence on other centers. After over investment in the early 2000s, Stockton was disproportionately affected by the 2007 economic crisis boasting the highest number of foreclosures in the United States that year. In 2008, Stockton’s housing prices fell by thirty-nine percent, the city’s foreclosure rate was almost ten percent (the highest in the country), and unemployment rate was over thirteen percent. Soon thereafter in 2012, Stockton became the largest city (at the time) in United States history to file for bankruptcy protection. After ranking second-place in 2008, in 2009 and 2011 Forbes awarded Stockton first-prize as America’s most miserable city, and in 2012 Stockton was ranked the tenth most dangerous city in America.

Ironically, these negative rankings are ultimately making Stockton an attractive destination for people fleeing an increasingly expensive Bay Area. The anticipated influx of people and investment makes Stockton a point of interaction between two Californias: the wealthy and scenic coastal strip along the Pacific and the poorer agricultural and industrial zone inland.

By developing design propositions for this site where rail, water, and money intersect in distinctive yet paradigmatic ways, the studio questions capitalism as a world-ecology, and it tests strategies for transforming this world-ecology through architectural form-making.