Greenville, California. Image credit: Janette Kim/Urban Works Agency.

property in crisis 3: Greenville

Curriculum: Advanced Architecture Studio, Fall 2023

Professor: Janette Kim

Studio Partner: Dixie Fire Collaborative and LMNOP.

Related Programming: After the Wildfire event at CCA

Students: Anastasha Aco, Xavier Bermudez, Francisco Calderon, Sebastian Cartright, Saulo Flores, Jennifer Guo, Melissa L Gomes, Chloe Hicks, Alexandra Huerta, Natalie Sofia Schtakleff, and Dipti Trivedi.

This studio is one of several architectural design studios at California College of the Arts working in partnership with community members in Greenville and Canyon Dam—two towns in Indian Valley that were nearly destroyed by the Dixie Fire. This semester, we focused on the design of affordable, workforce housing. We learned from our partners that the housing market is not supporting the development of workforce housing, even though the area’s economic vitality depends on workers. In response to this challenge, each student has proposed inventive property models that rework financing and ownership arrangements could support the creation of affordable housing. We then explored the architectural implications of these arrangements, bringing them to life as inhabitable spaces that shape social, urban, and ecological relationships. Ultimately, our goal was to help workers–and their family, friends, and people they care for–build equity, gain financial stability, and build a vibrant and resilient community. To see documentation of this studio’s process and a game we made to spark community exchange, please see this page.

1.Single Family Residential sites (R-7) in Greenville:

Pocket Living

by Melissa Gomes

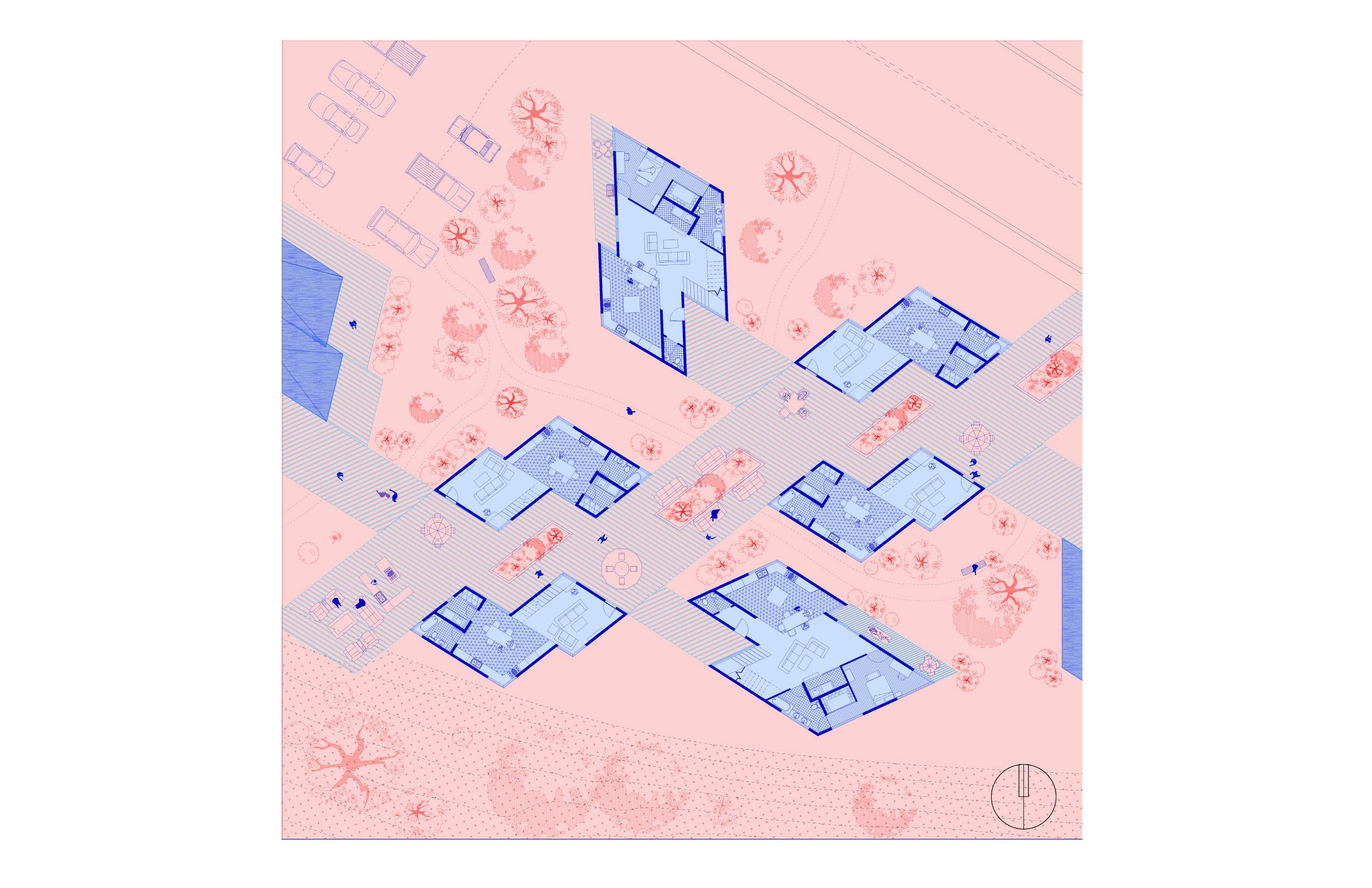

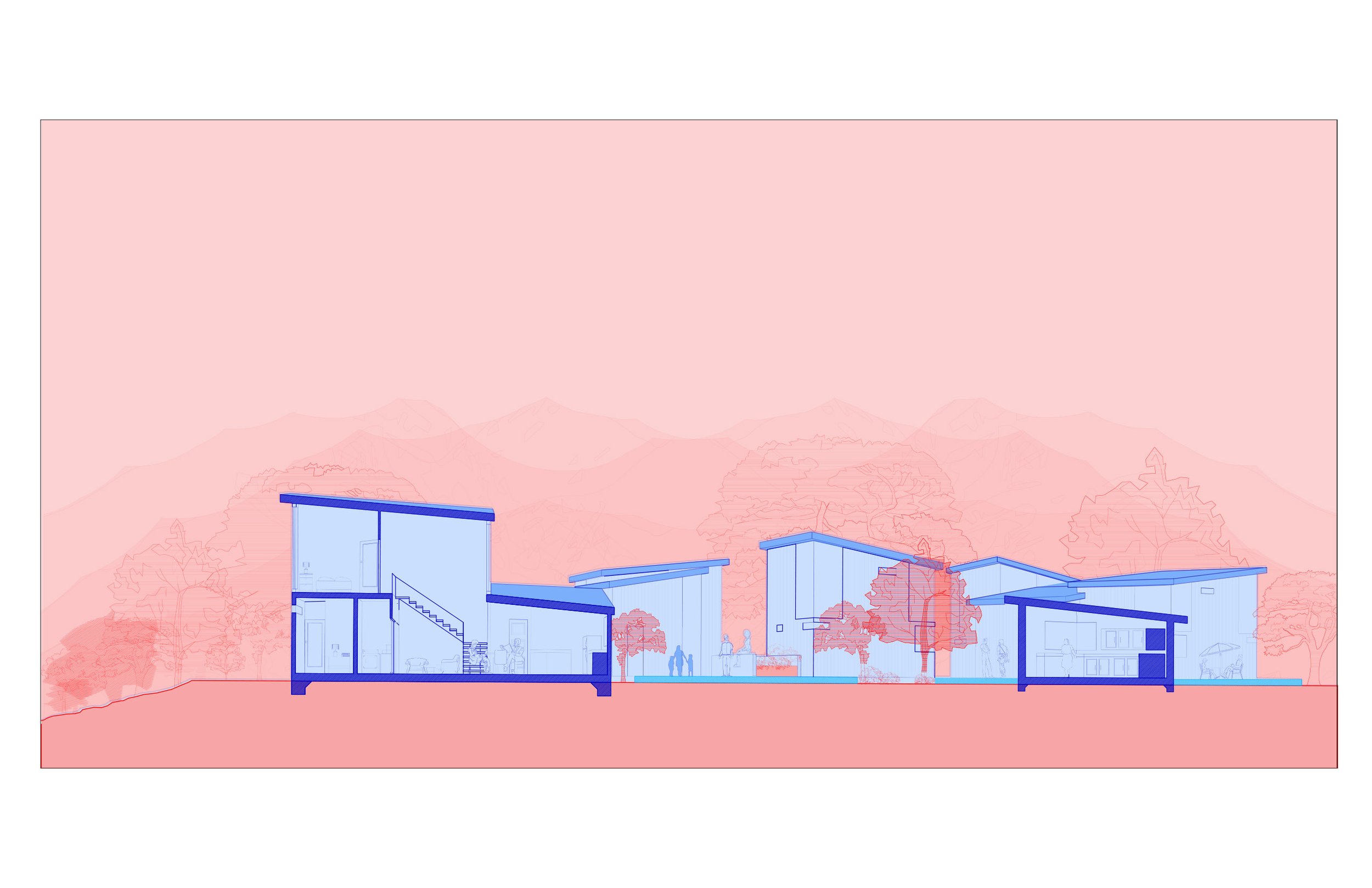

How can we make homeownership more accessible? In this project, Melissa Gomes has imagined a way to combine local, crowdfunded investments with time-share platforms like Airbnb and Vrbo. This approach could funnel local resources to new homeowners, who can build several housing units, provide affordable housing for their tenants, and generate profits for the homeowner and local investors alike. Melissa envisions a village-like community across two parcels, with one Main Dwelling unit and up to 3 accessory dwelling units on each (as allowed by the county’s zoning code). Although each unit has a unique entrance and private outdoor space, they engage each other across a shared plaza. Here, residents share lounge spaces, a fire pit, and an outdoor kitchen. Though they vary in their relationships on site, each accessory dwelling is identical, to enable prefabrication off-site and cut costs. Units are made of extra-thick walls that provide an eco-friendly shelter, storage, and reading nooks inside, and a BBQ pit, tool storage, and parking areas outside. From the scale of a drawer to the plaza, these pockets foster a sense of community among neighbors.

Housing Transitions: From Temporary to Permanent

by Xavier Bermudez

This project works with seasonal change to build mutually beneficial connections across four kinds of Greenville community members: current residents, seasonal workers, tourists and next-generation families. Xavier Bermudez’s design helps homeowners rent out seasonal housing while maintaining their own privacy and independence. In the summer, a gridded system of pocket doors can separate accessory dwelling units (ADUs) from the main dwelling, offering housing for seasonal workers and tourists. In the winter, the doors can open up, reclaiming space as part of the main dwelling. To make this affordable, Xavier Bermudez proposes a new zoning variance option. Currently, owners in R-7 (single-family residential) districts who own less than 1/7 of an acre can only build 3 units (a main dwelling, junior ADU, and attached ADU). Xavier’s proposal would allow the owner to build a fourth unit–a detached dwelling–if it is rented at a below-market rate. Ultimately, this arrangement would give the long-term homeowner the privacy and control they need while also supplying seasonal and flexible housing for the community.

Land Legacy

by Alexandra Huerta

This project responds to the loss of what Alexandra Huerta calls Greenville’s “endangered species”—its youth population. Alexandra Huerta imagines an ownership model she calls an Intergenerational Limited Equity Cooperative (I-LEC), or “Land Legacy.” An I-LEC leverages wealth from established resident owners to support an intergenerational community of low-income young adults and youth. Each cooperative combines 3 kinds of residents that support each other: established families, young families just starting out, and college students. Some own shares in the I-LEC purchased at a sliding scale, while others pay below-market rent to the cooperative. Individual housing units are arranged in a “Core-Pair” arrangement, with two separate units connected by an infrastructural core and shared outdoor spaces. This arrangement maintains individuality and independence while fostering shared living experiences, such as the option for a shared garden, laundry room or child care area in a roof deck between the two. The project, which spans several parcels, could be sited between Greenville High School and the four corners to foster intergenerational connections and revitalize the town’s social fabric.

Incremental Growth

by Anastasia Aco

Starting small is crucial to rebuilding a community like Greenville because it allows people to focus on immediate needs, build momentum over time, and create hope. When a community is devastated by a fire, there is often so much need that it can be overwhelming. By focusing on small, achievable projects, such as clearing debris or rebuilding a few homes, the community can make progress and start to feel like it is moving forward. In this project, Anastasia Aco proposes a clustered housing arrangement in which residents divide existing parcels into small lots to make land more affordable for low to middle income homeowners. Homeowners collaborate, too, as they would co-own the land in a Tenancy in Common (TIC) model, and can share resources and social support in spaces that scale up, from a courtyard between neighbors to a common garden shared across the city block. Aco designed a series of foundation walls that can make it easier to expand or infill housing over time. Working together on small projects can foster community spirit and a sense of resilience to revive and renovate their homes.

2. Recreation-Commercial Zoning (RC) in Canyon Dam:

Quercus Kelloggi Village

by Natalie Sofia Schtakleff

This project recovers land rights for Maidu people and prompts ecological restoration of the California black oak. Acorns from the black oak are cultural keystones, as they have shaped Maidu cultural identity in diet, material use, medicine, and spiritual practices. Natalie Sofia Schtakleff has designed a series of structures in Canyon Dam that create collective opportunities to tend and care for oaks. Buildings are arranged in a series of “L” shapes, forming double-height spaces where they intersect that connect cultural spaces on the ground floor to housing above. The L’s also create prong-shaped arrangements that frame adjacent landscapes of black oak and companion species. Indoor and outdoor spaces are also linked by curved walls–here, kitchens and event spaces support foraging, gathering, and cooking with acorns. To ensure this space engages a large and diverse membership base, Schtakleff proposes an ownership structure called a Permanent Real Estate Cooperative, or PREC, which allows Maidu community members, partnering non-profits, and residents alike to share in the governance of this site. They might, for example, partner with the US Forest Service in managing adjacent forested land. Ultimately, this space allows for healing, recovery, happiness and shared knowledge about this amazing group of people, the history of this land, and the future that it holds.

From the Ground Up

by Chloe Hicks

This project fosters a reciprocal relationship between the land and economy. It restores soil health, which was damaged by the Dixie Fire, by creating a lush, green landscape across a 4-acre site in Canyon Dam, which can, in turn, revitalize the area’s tourist economy. Chloe Hicks’ proposal imagines a new tourist center focused on outdoor recreation. A cafe, restaurant, convenience store, outdoor recreation store, bike shop, and hostel would serve both tourists and locals, across all four seasons.

Comm[UNITY]

by Jen Guo

Indian Valley has historically been rooted in its deep connection to the land–in raising animals, growing food, and harvesting wood–but is shifting focus toward recreation, tourism, and healthcare industries. Comm[UNITY] is a worker’s cooperative that helps entrepreneurs, artisans, and other small business owners transition in a changing local economy. In the summer, large, open spaces on the ground floor can host a recreation vendor market and recreation hub that connect tourists to local experts in fishing, mountain biking or hiking. In the winter, a more reduced building footprint hosts a job incubator, studio workspaces, and affordable housing to support business development and skill sharing among coop members. To make this all possible, Jen Guo proposes a Permanent Real Estate Cooperative (PREC) ownership model to ensure communal use, affordability, and a democratic collective governance structure.

Sprouting from the Ashes

by Dipti Trivedi

This project brings back Canyon Dam’s local economy by extending ownership to workers and by making the town a new hub for year-round activity. Here, Dipti Trivedi combines two cooperative ownership structures: a worker cooperative (in which workers share in the ownership of a business) and a Resident Owned Community, or ROC (in which members own homes individually and the land beneath their buildings collectively). Trivedi’s design clusters workshop and retail spaces on the ground floor with housing units above. Some clusters create a new village town square for visitors to gather, mingle, shop, and even enjoy a winter wonderland after a snowstorm, while others allow resident owners to mingle and share knowledge.

3. Multi-Family Housing Zoning (MC) in Greenville:

Community In Elevation

by Saulo Flores

Saulo Flores’ project is inspired by his conversations with Greenville residents, which revealed vivid memories of gatherings by the creek, social connections formed around food, and hopes for an enduring recovery. To support this desire, Flores proposed the creation of a Community Land Trust (CLT), in which residents would own buildings separately and land together. This arrangement would allow residents to share in the ownership of land, gaining autonomy and participation in a process of determining how Greenville is reconstructed. This arrangement would also give security for people who have not had access to homeownership, securing affordable housing across generations by capping its resale value. Flores’ design accentuates this relationship spatially. Each household owns one freestanding home, and engages the community along a deck that links gathering spaces both inside and out. Together, they are lifted off the land to respect the land they sit on and support the beauty that has drawn Greenville residents to this place.

Growing Care CLT

by Sebastian Cartright

This project supports single parents through a communal living arrangement inspired by Indigenous Maidu values. Since long before European colonization, Maidu communities have lived together in clusters of tight knit groups that nurtured the land with a recognition of its personhood. Here, Sebastian Cartright proposes the formation of a Community Land Trust (CLT) that can connect people to the land. As a first step, existing property owners would combine their assets and lay the foundation for future housing by constructing rammed earth walls. Next, as the CLT membership grows, co-owners can build cross-laminated timber housing structures above. Cartwright’s design imagines a chain of homes that form pockets between them for shared care-giving among neighbors. The pockets also open out to Wolf Creek, enabling residents to adopt a permaculture lifestyle on this fertile soil. Over time, bonds among neighboring children and parents can be strengthened, and co-owners can expand their homes to invite additional community members and provide housing for other care-givers.

Common Ground

by Francisco Calderon

Common ground invigorates Greenville’s local economy by building a new version of a company town. In Francisco Calderon’s proposal, new housing would be created through a partnership between landowners, who would provide the land, and a local business (such as a local timber mill), which would provide the capital. Both would and profit from rental income and, most importantly, the landowner can recover from the Dixie Fire with fewer up-front costs while the business can attract workers to the area. Workers would play a critical role too, with the power to vote on rules governing the cooperative, and with a rent-to-own feature that would enable them to earn ownership of their homes over time. They would gain autonomy and stability that is reflected in Calderon’s design. Here, each building is cut into the site to provide private spaces overlooking Wolf Creek, while a communal deck links the homes as one community.

A note for community members: To guide our process and explore the projects’ potential for implementation, we identified three kinds of sites whose zoning regulations work especially well for workforce housing. We chose a few properties as pilot sites. But don’t worry–we’re not trying to change your home!! We hope to test to our ideas here to see how they might apply to other sites with similar conditions in the future.