Image credit: Janette Kim / Urban Works Agency

Property in Crisis

Curriculum: Advanced Architecture Studio, California College of the Arts, Architecture Division

Date: Fall 2020

Professor: Janette Kim

Students: Sanyukta Bhagwat, Craig Dias, Jason Gonzalez, Shih Ting Huang, Chaitanya Khurana, Savannah Lindsey, Kyle Matlock, Kevin Pham, Abigail Rockwell, Alexander Roos, and Marion Rosas.

Studio Partner: East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative

Related Programming: Reclaiming Land Symposium

Property is power. The subdivision of land as ‘property’ has defined racial and social justice—and injustice—by shaping the way wealth is created. The Jeffersonian grid, for example, accelerated the seizure of Indigenous land and lives in the colonial settlement of the American West. The single-family home banked on discriminatory loan policies and zoning laws that ban affordable housing in the name of protecting property values. These and many other exclusive systems still endure, preventing Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color from generating wealth.

In today’s ‘risk society,’ this legacy of social injustice leaves precarious communities even more vulnerable to ever-mounting threats of climate change, economic volatility, and defunded public health systems. Politicians and planners have famously portrayed these risks as an ‘opportunity’ for wholesale change—but as the demolition of viable housing after Hurricane Katrina showed, crisis has also been used as a convenient smokescreen to further self-interest. Others have promoted ‘resilience’ as a way for vulnerable communities’ ability to bounce back from tragedy, but have been sharply criticized for failing to prevent such losses in the first place. Instead, a community’s true ability to withstand crisis requires reconciliation with past injustices as well as contemporary volatility. It demands a more inclusive cultivation of wealth and power—one possible in the reconfiguration of property.

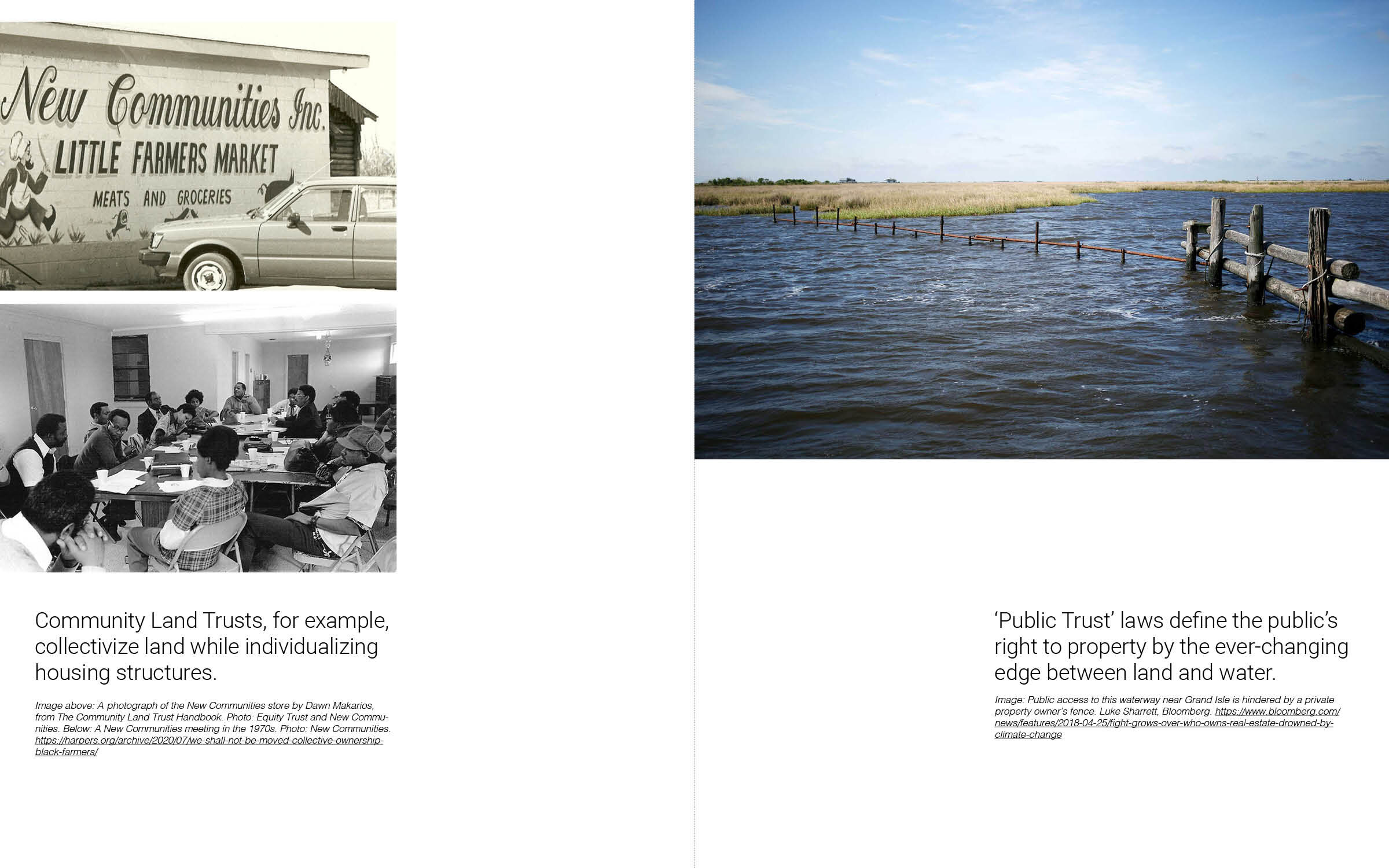

There is, in fact, a flip side to property. Many of its underlying logics—such as the commons, liability, maintenance, belonging, and yes, even profit—can also be altered towards more inclusive ends. Community Land Trusts, for example, collectivize land while individualizing housing structures. ‘Public Trust’ laws define the public’s right to property by the ever-changing edge between land and water. Such alternate property arrangements can launch deep-seated, systemic reform, prompting social exchange, cultural expression, alternate economies, and ecological vitality.

Such arrangements require an entirely different spatial condition, from the scale of the kitchen table to the rooftop to the watershed. In this studio, we will invent new alignments and misalignments across water, land, foliage, foundations, walls, roofs, furniture, and fixtures. Though property has long assumed a one-to-one correspondence among all of these elements, it is up to designers like you to imagine a far different paradigm.

This studio asks how property can be reimagined in the face of crisis to strengthen racial and social justice.

The gallery of images shown here describes the background to this studio, and shows a ‘Property Playbook’ created by the students. The playbook is composed of a deck of cards that show how diverse systems of land ownership can support social justice. Some strategies collectivize financial risk and responsibility (East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative, Fujian Tulou, Micro-Financing, Accessory Dwelling Units), while others expand resource rights (Usufruct Rights, Energy Cooperatives, Air-Rights Transfers) or leverage temporality (Public Trust Doctrine, Airbnb, and Vacancy Taxation). And coming soon, we will also post site acquisition and design proposals from the students here.