RESILIENT EQUITY HUBS

Faculty Research

Date: 2018-current

Principal Investigator: Janette Kim

Resilient Equity Hubs (REHBS) is a speculative design proposal that imagines collective ownership and management of land to support social equity in the face of climate risk. The work shown here expands on urban design strategies that initially emerged in collaboration with The All Bay Collective, in the Resilient by Design Bay Area Challenge (2017-18)

Stewart Brand, in his “Shearing Layers” diagram, famously unpacks the incremental manner in which buildings change over time. Stewart Brand famously expanded on architect Frank Duffy’s theories to create his “Shearing Layers” diagram, which outlines six building components--stuff, space plan, services, skin, structure and site--ranked by their longevity and “organizational levels of responsibility.” Brand peels away these layers to enable its inhabitants to transform them, deliberately and affordably. This process would put the user in charge, and spark a process of trial and error that can truly adapt to change. Importantly, however, Brand declares that “site is eternal” and property is “inviolate.” The same techniques of manipulation he embraces at an architectural scale are, to Brand’s libertarian mindset, intrusive to one’s right to self-sustenance and self-determination at an urban scale. What Brand doesn’t recognize is that transient elements of the built environment embroil unseen side effects, benefactors and multiple collectives beyond the boundaries of the building’s own lot.

A decidedly more ambitious application of How Buildings Learn, then, would point Brand’s same delamination techniques to the political valences of site. These complex systems not only have their own period of change, but a tangled web of ownership, maintenance, regulation, and other forms of interest across publics, governments, and utilities. Property is the critical link here. Far from being a sanctuary from intrusive forces, property is exactly the dynamic, malleable component of the city that can welcome new custodians. It is just the medium that can draw lines of inclusion among previously disinterested subjects, or spin off overbearing entanglements from those at greatest risk. In this sense, the duplicity of resilience be replaced with a capacity to adapt without accepting failure.

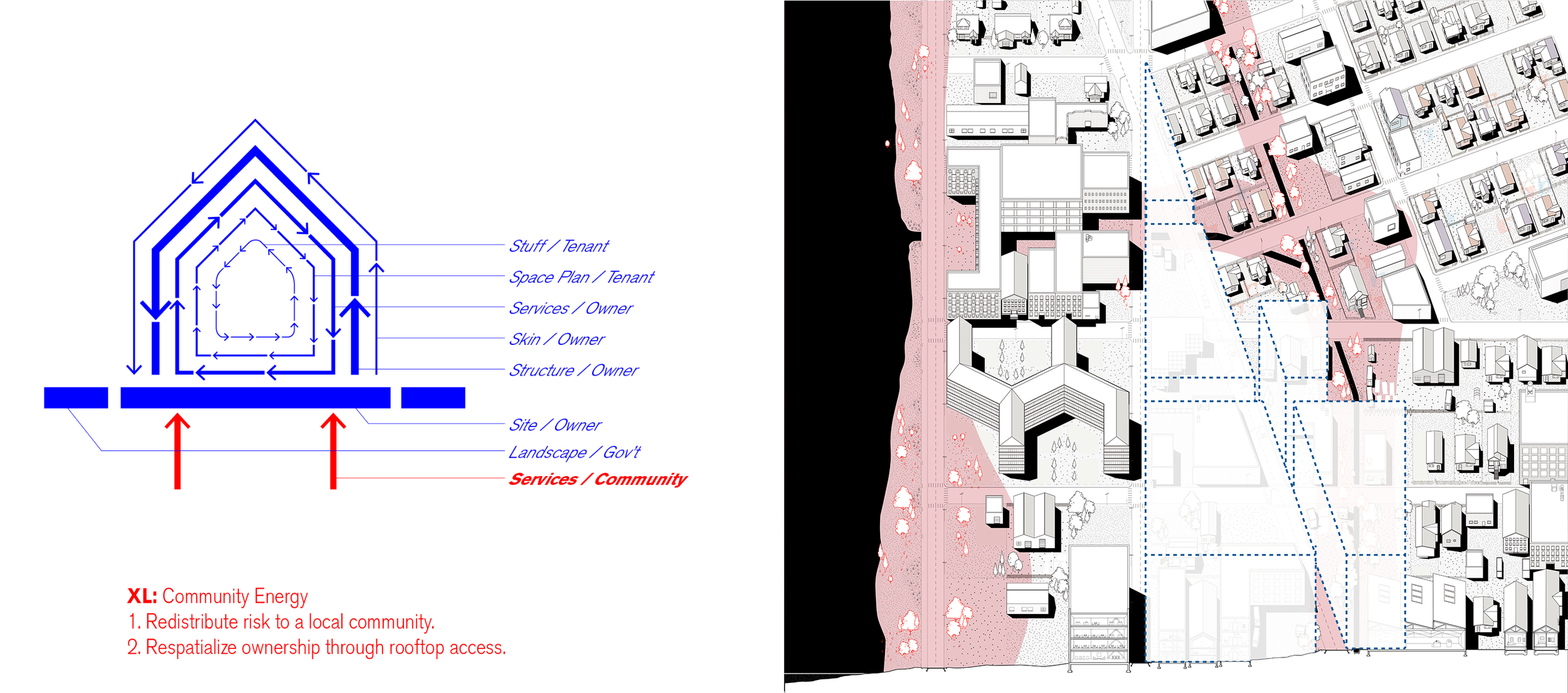

To test the architectural implications of such arrangements, this project reapplies Brand’s Shearing Layers diagram to the city. We began by redrawing the diagram to peel apart layers of the site. Sidewalks, roads, sand dunes, wetlands and utilities each have their own rate of change and overseers, from the Army Corps of Engineers and Business Improvement Districts to privatized utility companies. Each layer has different beneficiaries and benefactors. Next, I set up five speculative scenarios in which innovative financial and legal models can reconfigure the rewards and obligations of ownership. These scenarios build on strategies our team and partners developed for the Resilient by Design Challenge, and imagine in each case who is responsible, who shoulders the burdens of risk, and how ownership can be spatialized. Each scenario is illustrated with an updated diagram and a drawing of its enactment in a fictional urban landscape.

The first scenario imagines the application of the public trust doctrine to open up land to ownership and management by the state. The public trust doctrine, which stems from English colonial law and Roman law before that, gives the government the right to hold property that sits below the average high tide line. In a manner that has curious affinities to Brand’s own time scales, the law is only applicable if the tide line migrates slowly, as with climate change, rather than quickly, as in a sudden storm or levee failure. In places like the Mississippi Delta, use of this law would not only open up waterways to public recreation and fishing access, but also oil fields to government profit, seizure or restoration. In this drawing, the public trust doctrine would enable the state to peel away corners of urban blocks (shown in pink) below the water line while still allowing private ownership to prop itself above. This patchwork of public lands could widen flood channels or enable groundwater to pool, thus alleviating pressures on adjacent properties, and create neighborhood centers that support social infrastructure.

Second is the use of value capture financing like a Community Benefits Agreement. Such an agreement, which I mentioned above as a central element to our team’s Resilient by Design Challenge proposal, can leverage anticipated increases in real estate value (shown in dotted lines) to create a fund that can be run by a community-based participatory budgeting process or nonprofit. Residents could decide over time how to invest in areas shown in pink, such as affordable housing, grants to small businesses, subsidized day care centers, or wetland restoration for example. Spatially and financially, this creates an exchange across the neighborhood rather than pitting future development against existing community interests, and creates a scaffold for incremental change and hybrid land uses.

The third scenario depicts a community-owned solar installation across a network of rooftops inspired by the Oakland Climate Action Coalition’s work to do the same in East Oakland. Community-owned solar allows tenants and owners alike to invest in an array of solar panels distributed across rooftops held by various owners (shown in yellow, blue and pink). Members of this cooperative can invest, govern, and maintain this solar farm and profit directly from energy sold through a larger municipal grid. It can also reduce green-house gas emissions and thus play a role in dampening the effects of climate change, and stay running even during a system-wide blackout. Public energy, in this sense, allows individuals to build equity from common, natural resources. Here, such a collective network becomes visible across an expansive rooftop landscape.

In the fourth scenario, a community land trust, land is owned collectively (shown in yellow), while buildings are owned individually (red and blue). Homeowners can pool resources to waterproof buildings, lift foundations and share in the maintenance of a landscape that can be aggressively reshaped and reconfigured to welcome in the floods. No one landowner alone would bear the cost of rising insurance or pumping out groundwater. CLTs can also build new housing on higher ground to make way for groundwater ponds or to welcome in the tides. And because CLTs limit resale value to resist speculative pressures, housing can stay affordable while enabling residents to build equity and stay in the neighborhood despite development or flooding pressure.

The fifth scenario depicts a Micro-financing ownership model, in which individuals can purchase shares of a property. Micro-investment might be structured through apps that might sell $5 shares in a luxury apartment or—in a far less speculative mode—initiatives like the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative that pool small investments from local community members to provide affordable housing for people of color. EBPREC invites “investor owners” who contribute $1000 to share in the governance of affordable housing alongside “resident owners” and “staff owners” with equal votes. Micro-financing diffuses the interests of homeownership from the singular title-holder to a community that stands to benefit from greater social equity. Spatially, such a model could be enabled by creating scalable pockets of collective space that might carve out interior pockets or scatter investments throughout the city.

Each of these scenarios diffuses the risk of ownership and extends its rewards to a broader flock of beneficiaries. These innovative spatial and social arrangements locate power within the intricately interconnected cultural, spatial and economic logics of property.

Project Credits: Janette Kim/Urban Works Agency, with Clare Hačko and Cesar Lopez.

For other UWA work on property, see the Reclaiming Land symposium, and the Property in Crisis studio.