retrofitting work

Curriculum: Advanced Studio

Date: Fall 2024

Professor: Janette Komoda Kim

Student Authors: Abby Van Kirk, Alana Abuchaibe, Amanda Gomez, Clarice Gaw Gonzalo, Gaoyang Dong, Jongmin Jeon, Marcus DMattus, Nathan Buenviaje, Salwa Shafiq, Shinnosuke Nomura, Vicky Cheung, Ziching Ooi.

The world of work has changed a lot recently. As the American economy has shifted from industrial to service and knowledge economies, we’ve seen stable, salaried jobs give way to more flexible employment, often as freelance or gig labor. This new economy offers its workers creativity, mobility, and self-determination, but with the added burden of financial precarity, exhaustion, and anxiety. The pandemic brought this all into sharp relief, exposing the public’s dependence on essential (but undercompensated) labor and raising questions about work/life balance, as remote work brought mixed results and millions voluntarily left the workforce in the “Great Resignation.” As new as these dynamics are, however, they also resonate with long-standing questions about work. How might work restructure class hierarchy, resist normative gender roles, and legitimize informal labor? How can workers be empowered through ownership of the means of production? How can knowledge and the products of our labor be shared, and what kinds of communities form in the process?

Students in this studio were asked to rethink the meaning, ethics, and culture of work. We focused on one industry–the baking, distribution, and enjoyment of bread. From vendor stalls to GrubHub and the Bimbo bread empire, this industry will allow us to explore diverse forms of ownership; creative forms of solidarity around class, race, and gender; worker creativity and agency; and community formation.

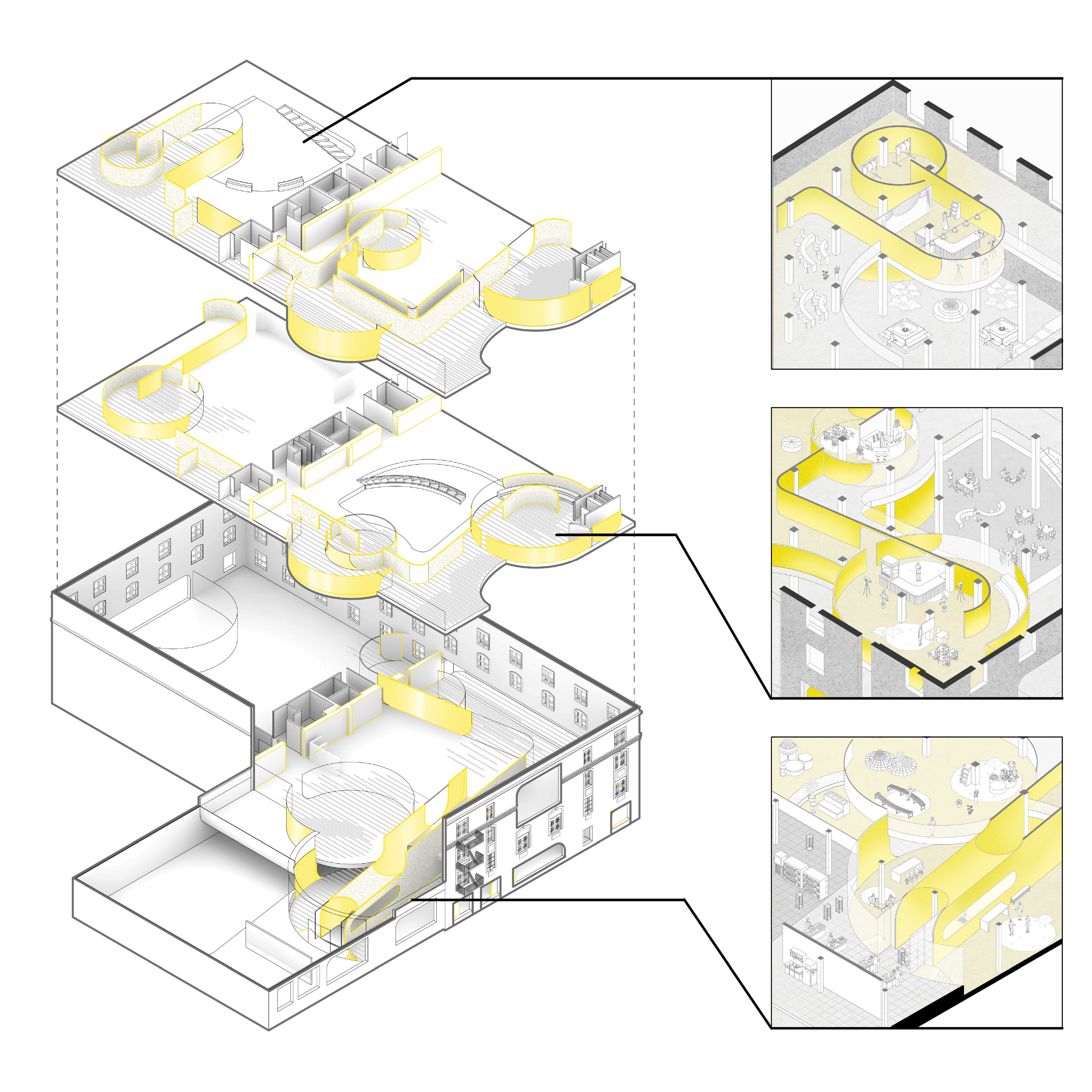

How can we rethink work? This studio was based on the belief that we can only meaningfully alter work by addressing systemic economic and social conditions that unfold in urban spaces. Students conducted cultural research, urban analysis and design at the scale of one urban block in San Francisco. We then adopted retrofitting and adaptive reuse techniques to alter, subtract from, and add to multiple, existing buildings across each urban block. We thus edited existing urban fabric instead of building anew. Retrofitting and adaptive reuse are often celebrated for their preservation of cultural heritage and their reduced environmental footprint. Additionally, and most importantly for our studio, these techniques allowed us, as designers, to consider how society changes.

We focused on sites across San Francisco with significant legacies of labor and work from of their previous use. In 1890’s Haight Street, for example, small businesses clustered around ornate homes where domestic workers performed housework in the basement. In the 1900’s Tenderloin, residents of single-room occupancy buildings used diners and saloons as their living rooms. In 1950s South San Francisco, a large-span warehouse next to suburban worker’s housing supported mass-scale production. And in 1990s SOMA, open-office floor plans fostered collaboration among marketing creatives. Today, these spaces host artisanal bakeries, malls, restaurant incubators, tech company headquarters, and multinational corporations. What can they support in the future? By employing very tangible architectural moves–by subdividing, encasing, or recombining these spaces–we can envision inventive program typologies and alternate narratives, and thus enable a new ethic of work to emerge.

Images: 1-4 Clarice Gaw Gonzalo, 5-7 Gaoyang Dong, 8-10 Vicky Cheung, 11-14 Salwa Shafiq, 15-18 Zicheng Ooi and Nathan Buenviaje, 19-20 Jongmin Jeon.