Reynolds Metal Company Housing (Jackson, MS., 1950s), 60 Richmond Hospitality Workers Housing Cooperative (Toronto, Canada, 2010), Facebook-financed Anton Menlo Housing Development (Menlo Park, CA., proposed)

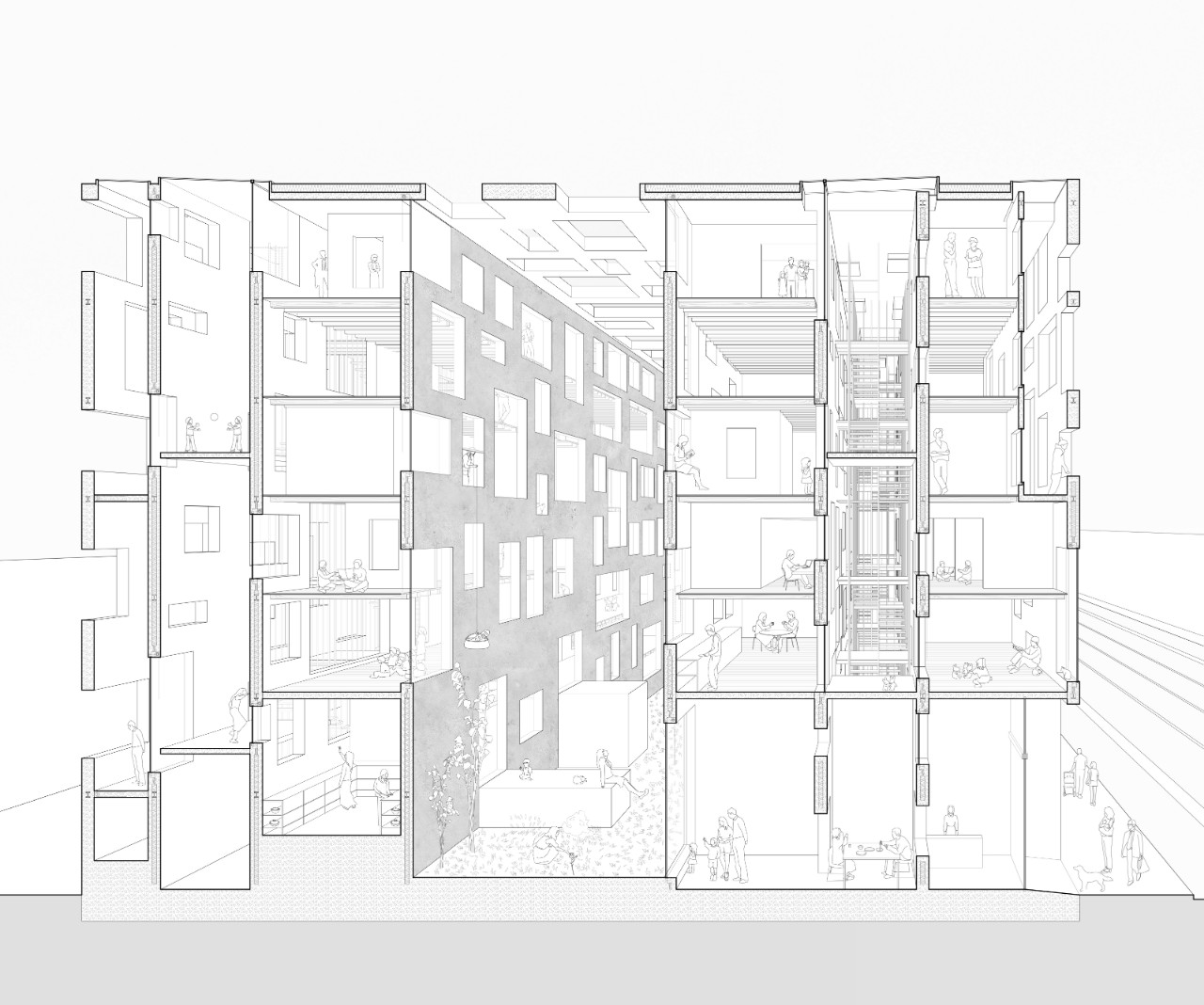

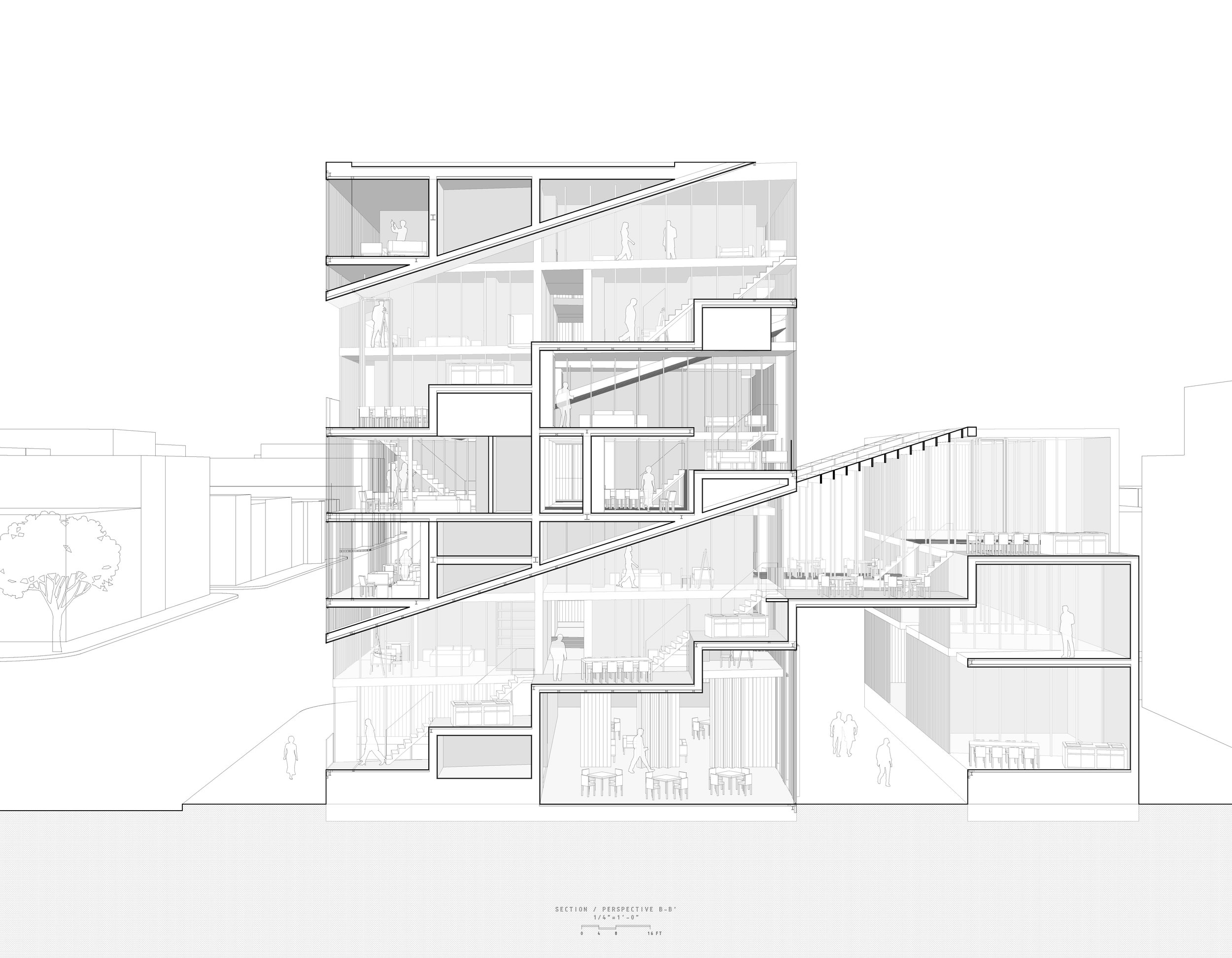

The Vertical Collective

Project: Workers’ Housing in the Contemporary City

Class: BArch Studio 4, California College of the Arts, Architecture Division

Date: Spring 2017

Instructors: Antje Steinmuller, Chris Falliers, and Inaqui Carnicero

This fourth and last of the architecture core studios understands architecture as a political tool in an urban context. The studio understands itself as a transition between core and advanced studios: it emphasizes the formation of a clear, critical position towards a specific urban issue as an integral part of each student’s design proposition. The studio focuses on the investigation of the political power of architecture in a complex urban project that addresses specific current issues in CCA’s immediate surroundings – the city of San Francisco. Architecture, by its very nature, gives form to spatial relationships and hierarchies. As such, it engages in the distribution of spatial resources in the city. In San Francisco, where space has become an expensive commodity, rethinking how we use and share space through the lens of architecture, therefore, becomes a political act.

This semester, the studio take on the topic of worker’s housing in the contemporary city. Worker’s housing social housing, or live-work are terms loaded with associations of economic classification, homogenous and/or isolated communities, government bureaucracy, and/or real estate speculation. In each case, designs for habitation for a certain segment of the population evolved into a spatial and procedural type. Yet, the terms often bring up negative connotations of blandness, impersonal, unclaimed space, cheap construction, and deteriorating social/spatial conditions.

These housing types became subjects of exploration most often to meet a changing urban demographic. During the mass-migration for Industrial Revolution-era jobs, factory owners built workers housing near their factories to accelerate production. Some state authorities conceived of workers or social housing in an exemplary model of political doctrine. Other government agencies commissioned state-designed housing as part of policies for social reform and urban renewal. Live-work typologies evolved as meeting a demand for urban-chic habitation, while it leveraged building-code loopholes on adequate access to natural air and light. Temporary farm workers housing addresses seasonal needs for accommodation in close proximity to the work place via the provision of a minimal, shared infrastructure to keep rental cost low.

From Le Corbusier’s Cité Frugès (housing for sugar factory workers, 1924) in Pessac, to Moisei Ginzburga’s Narkomfin building (housing for employees of the Commissariat of Finance, 1930) in Moscow, early workers housing commissions presented an opportunity to put into practice avant-garde theories on architectural form and communal living. Ginzberg conceived of Narkomfin as a social condenser, confining private amenities to a single cell while kitchens and living areas were designed as collective spaces. While initially rejected by the original inhabitants, these ideas are increasingly gaining popularity today – among the generation of artists and urbanites who occupy these buildings, and among contemporary architects who investigate housing typologies beyond the nuclear family.

As the need for housing in San Francisco, one of the most expensive cities in the world, is again acute, the sharing concepts and socio-spatial experiments of early workers housing have gained new relevance. Attracted by employment tax breaks, more and more large tech companies have made their headquarters in San Francisco, while the city also still offers an ideal environment for new start-ups. With the influx of new types of (tech) workers came the (re-)emergence of intentional communities formed around similar (work/) life-styles. At the same time, the city has struggled to maintain economic and social diversity among its inhabitants as rising rents are displacing entire segments of the population. The origins and contributing factors of San Francisco’s housing crisis are complex, and the housing crisis goes beyond a local or regional problem, affecting many cities in the US and globally. As (aspiring) architects we likely cannot solve the interdependent underlying issues. But, we can contribute ideas that opportunistically explore strategies rooted in our discipline-specific knowledge: innovatively rethinking spatial, programmatic and organizational approaches to housing in the age of the sharing economy.”

_the proposition

In the specific context of San Francisco, this studio will revisit the notion of workers housing along three conceptual axes that respond to ongoing housing-related processes in the city:

1. the tech domestic: contemporary understandings of changing relationships between the domestic and the workplace in the age of hacker hostels, nap spaces and free food in tech company culture, and transitional/temporary housing needs for mobile employees of globally positioned tech companies.

2. social housing 2.0: responses to the displacement of blue-collar workers from the city that positions space sharing concepts as a way to more affordability.

3. live-work-share: addressing the needs of urban creatives in a city where live-work loft typologies have become luxury commodities for the privileged few.

While Facebook plans to co-finance Anton Menlo, an apartment complex at a 5-minute bike ride from its Menlo Park campus that offers a pool, sports bar, and doggy day care and is likely to become a de-facto company housing estate in the suburbs, the conceptual trajectories of this studio aim to produce contemporary typologies for urban workers housing – typologies that address affordability, new types of community, and integral connections with the surrounding city.